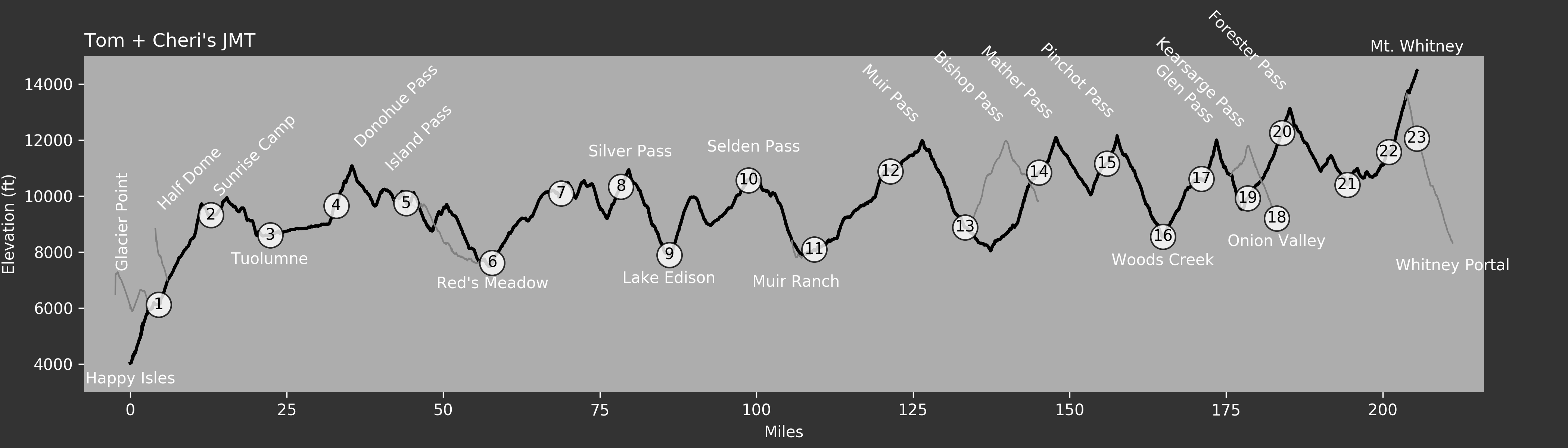

The John Muir Trail links Yosemite Valley with the summit of Mt. Whitney, the highest mountain in the contiguous United States. It extends for more than 200 miles through forests, alpine meadows, and rocky passes of the high Sierra. It’s a singular destination for backpackers, and one that’s loomed large in my ambitions for many years.

In 2016, Cheri and I had the opportunity to hike its entire length from north to south. We lived on the trail for 24 days and 23 nights, averaging 10 or so miles per day while eating our way through four food resupplies. Along the way, we summitted Half Dome, swam in cold alpine lakes, forded some formidable streams, and ended with a pre-dawn climb of Mt. Whitney. On no day did we lay over – we moved the tent every day.

The trail is very popular. We met dozens of people daily, ranging from those doing extended weekend loops, to fellow JMT hikers, to Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikers on their way to Canada. A permit system limits the crowds. Cheri and I spent a week in early January faxing a permit application to the Park Service each day until we were selected. We spent the next few months poring over maps and dehydrating as much food as possible.

We planned for four food resupplies, mailing one to the Muir Trail Ranch and leaving the rest in the hands of Cheri’s parents, who would meet us at each of our other rendezvous points: Tuolomne, Red’s Meadow, and Onion Valley. They also ferried us to Yosemite and from Whitney Portal, making a driving tour of California while we hiked. I could not imagine having a better support team than Bill and Carol, and we owe them big.

Our permit stipulated that we start at Glacier Point, rather than the official trailhead at Happy Isles, so we spent our first day walking the spectacular Panorama Trail to Little Yosemite Valley. This alignment also cut about 2000 feet of elevation gain out of our first day, making it one of our most leisurely days on the trail.

Our second day was anything but leisurely. In the morning, we made a side hike up the cables route on Half Dome, which I found utterly terrifying, even as a rock climber. I found very little traction on the polished granite surface, so I hauled myself up by holding the cables in a death grip, shredding my hands in the process. Many day hikers bring gardening gloves to protect their hands from the cables, and if I did it again I would too. Fortunately we avoided most of the crowds by starting early in the morning, and only had to pass about four people on the way down.

A grueling afternoon climb delivered us to the Sunrise High Sierra camp, a gorgeous meadow inhabited by the worst swarm of mosquitoes I have ever met. We cooked dinner quickly and retreated into the tent, and I thanked Cheri for having dissuaded me from doing this hike with a meshless tarp tent strung between my trekking poles. Throughout the rest of our trip, the mosquitoes were frequently terrible, but never worse than they were at Sunrise.

We bought mosquito netting in the store at Tuolomne the next day. Cheri’s parents spoiled us at the restaurant there and gave us our first resupply. Tuolomne is where the JMT makes its junction with the Pacific Crest Trail, and from then on we were frequently meeting northbound PCT hikers heading the other way (except for my friend Mike, whom we missed by a few hundred yards).

The trail is punctuated by many high mountain passes, which we tried to get over in the mornings to avoid being left exposed in an afternoon thunderstorm. Only one thunderstorm ever did hit us, and that was on our fifth day after having crossed both Donohue and Island passes that morning. We got the tent up just in time, but in our haste we picked a bad spot and our tent flooded an inch or two deep. A couple friendly guys from the next site over helped to bail us out before nightfall. The sun dried everything out the next morning and we had perfect weather for the rest of the trip.

We didn’t plan on staying the night at Red’s Meadow, but running from the thunderstorm put us a little ahead of schedule and we decided to surprise Cheri’s parents by rolling in the evening before our previously-scheduled rendezvous time. I’m glad we did, because Red’s is probably the most hiker-friendly resupply point on the entire route. We had a nice shower and even inherited a cabin from a friendly dentist who had rented one and then decided not to sleep in it.

After leaving Red’s, we had the sense of being much deeper in the wilderness. Bridges became less common, and stream crossings became a regular obstacle for us. Rather than risk losing our camp shoes in the current, we waded through barefoot, which was uncomfortable but okay. I was very happy to have poles with me to navigate the big crossings like the one at Bear Creek. We got in the hang of living on the trail, and settled into a rhythm of moving through ever more spectacular spaces. We loved camping in the high alpine areas, swimming in the lakes, and admiring the alpenglow over the meadows at night.

Muir Trail Ranch, a commercial outfit located just past the trail’s midpoint, is less nice than Red’s, but popular with hikers because it is the last easy resupply on the JMT. We joined several dozen other hikers here in picking up our supply bucket and trading away our less favorite foods. Carbohydrate was flooding the market and we held tight to our blocks of cheese and salami. I turned down a deal on Nutella for possibly the only time in my life and donated an extra bottle of olive oil to a PCT hiker who was only there to scavenge from JMT hikers who had mailed themselves too much. The staff is picky about accepting trash, and when I asked for the toilet I was instructed to dig a hole outside the gate. I was glad to get back on the trail.

In its second half, the JMT passes into King’s Canyon National Park, a vast tangle of valleys and passes far from any road. As the trail snakes through Evolution Basin, Le Conte Canyon, and the Palisades, only the occasional backcountry ranger residence is any sign of civilization. In the seven days we took to hike this section, we crossed four 12,000 foot passes: Muir, Mather, Pinchot, and Glen.

About a week into July, the PCT crowd started to thin out. We met one guy at Pinchot pass who was out here with no lighter. We traded him one of our extras for a bag of skittles.

I was fascinated by the continually changing character of the rock and biome. Evolution Basin had a barren, polished personality, while Le Conte was thickly forested. By the time we reached Pinchot, the mountains took on a reddish, crumbly, almost Coloradan character. The sparse vegetation was mostly scrub, interspersed with really gnarly-looking trees.

I found the second half of the trip to run a lot smoother than the first. We had our system dialed in so well that the miles just kind of disappeared. We arrived at Rae Lakes with the day only half over, and spent the entire afternoon napping, reading, swimming, and exploring the neighborhood.

Some groups hike from MTR clear to the end without resupply, either by running thin or rolling heavy. Running thin would have meant rushing through the last 100 miles in seven days, while rolling heavy would have meant carrying more food than could possibly fit in our (dual BV500) bear cans. We met groups who took both approaches and were happy to have done it differently.

We hiked off the JMT to Onion Valley, a high trailhead in the East Sierra, via Kearsarge pass. This is the same route taken by mule trains that wealthy hikers hire to carry food in for them. It added about a day and a half to our route, but it was scenic and not at all miserable. Here we had our third rendezvous with Bill and Carol and picked up our final resupply from them at the campground.

The weather report we got at Onion Valley claimed that we’d see clear skies for the rest of the trip, so we rolled the dice by sleeping high above treeline on our 20th night. We camped on the shore of an unnamed lake just below Forester Pass, the highest and final of the JMT’s passes before reaching Mt Whitney.

After crossing Forester pass we entered Sequoia National Park. None of its namesake trees can grow this high in the Sierra. Instead, the trail travels through miles of wide-open meadow.

An easy two days’ hike from Forester brought us to Guitar Lake, a nice warm lake with many campsites located on the west face of Mt. Whitney. We rested up here for our summit day.

We packed up our camp at 2:00 in the morning in hopes of making it up Mt. Whitney in time for the sunrise. The moon came out about an hour later, but while switchbacking up the west-facing slope we remained in the shade. We felt strong and very well acclimatized, but it became clear that we were cutting it kind of close.

Many backpackers leave their bags at a trail junction 1,000 feet below and 2 miles short of the summit, where the JMT joins the Whitney Portal trail. By the time we got there we didn’t have 10 minutes to spare, so rather than sorting through what to leave and what to bring, we just carried everything to the summit. We made it just in time.

<

<

Ever since the fourteener-obsessed days of my youth, I’ve aspired to climb Mt. Whitney. It was a joy to do it as the capstone to the longest, most wonderful hike of my life.

Officially, the JMT ends here, but the exit trailhead lies some 6000 feet below, at Whitney Portal. After soaking in the view from the highest point in California, we set off down the trail past the scores of day hikers coming up from the East side. We spent one more night on the trail before exiting at the portal.

I’m incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunity to hike the JMT, and I’m grateful for everything that made it possible. Here is our itinerary:

| Day | From | To | miles | Gain (ft) | Loss (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glacier Point | 01 Little Yosemite Valley | 7.1 | 2160 | 2525 |

| 2 | 01 Little Yosemite Valley | Half Dome | 3.4 | 2801 | 101 |

| Half Dome | 02 Sunrise Camp | 9.0 | 2931 | 2452 | |

| 3 | 02 Sunrise Camp | 03 Tuolomne Meadows | 9.4 | 1232 | 1817 |

| 4 | 03 Tuolomne Meadows | 04 Lyell Fork Bridge | 10.1 | 1429 | 377 |

| 5 | 04 Lyell Fork Bridge | 05 Garnet Lake | 11.2 | 2801 | 2707 |

| 6 | 05 Garnet Lake | 06 Reds Meadow | 14.4 | 2397 | 4408 |

| 7 | 06 Reds Meadow | 07 Below Duck Lake | 11.2 | 3090 | 737 |

| 8 | 07 Below Duck Lake | 08 Squaw Lake | 9.6 | 2806 | 2577 |

| 9 | 08 Squaw Lake | 09 VVR Junction | 7.8 | 980 | 3395 |

| 10 | 09 VVR Junction | 10 Marie Lake | 12.8 | 4087 | 1423 |

| 11 | 10 Marie Lake | Muir Trail Ranch | 7.7 | 682 | 3503 |

| Muir Trail Ranch | 11 Piute Creek | 3.2 | 653 | 329 | |

| 12 | 11 Piute Creek | 12 Evolution Lake | 12.2 | 3548 | 742 |

| 13 | 12 Evolution Lake | 13 Le Conte Canyon | 12.0 | 1730 | 3737 |

| 14 | 13 Le Conte Canyon | 14 Palisade Lakes | 11.8 | 3526 | 1549 |

| 15 | 14 Palisade Lakes | 15 Lake Marjorie | 10.8 | 2572 | 2225 |

| 16 | 15 Lake Marjorie | 16 Woods Creek | 9.1 | 1302 | 3944 |

| 17 | 16 Woods Creek | 17 Rae Lakes | 6.3 | 2348 | 298 |

| 18 | 17 Rae Lakes | 18 Onion Valley | 12.4 | 3256 | 4695 |

| 19 | 18 Onion Valley | 19 Upper Vidette Meadow | 10.5 | 3559 | 2845 |

| 20 | 19 Upper Vidette Meadow | 20 Below Forester Pass | 5.6 | 2475 | 173 |

| 21 | 20 Below Forester Pass | 21 Wallace Creek | 10.5 | 1528 | 3418 |

| 22 | 21 Wallace Creek | 22 Guitar Lake | 6.7 | 1895 | 726 |

| 23 | 22 Guitar Lake | Mt. Whitney | 4.6 | 3139 | 272 |

| Mt. Whitney | 23 Trail Camp | 3.7 | 486 | 2853 | |

| 24 | 23 Trail Camp | Whitney Portal | 5.8 | 195 | 3896 |

| Grand Total | 239.0 | 59606 | 57724 |

Glacier Point

- 24 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Glacier Point

- 24 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Panorama Trail

- 24 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1900s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Panorama Trail

- 24 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1600s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Little Yosemite Valley

- 24 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/80s f/4.5 at 24mm iso400

Scoping out the cables

- 25 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Cables route, Half Dome

- 25 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Half Dome summit

- 25 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Half Dome summit

- 25 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/4000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Descending the cables

- 25 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/3700s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Swarmed by mosquitos at Sunrise High Sierra camp

- 25 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Sunrise High Sierra camp

- 26 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso800

Leaving Sunrise High Sierra camp

- 26 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso800

Frosty meadow near Sunrise High Sierra Camp

- 26 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso800

Cheri

- 26 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Cathedral Lake

- 26 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Peak PCT hiker season at the Tuolomne post office

- 26 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/30s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso64

Lyell Canyon

- 27 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2200s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Night 4 at the Lyell Fork bridge

- 27 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Donohue Pass

- 28 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1250s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Donohue Pass

- 28 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/2500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Donohue Pass

- 28 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/11.0 at 24mm iso100

Thousand Island Lake, Banner peak, and the beginning of a major thunderstorm

- 28 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/5900s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Drying out from the storm at Garnet Lake

- 29 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso200

Rosalie Lake, our favorite swim

- 29 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/850s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Leaving Red's Meadow

- 30 June 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2000s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

- 30 June 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1250s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Cheri at Squaw Lake camp

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1600s f/4.0 at 24mm iso100

Cheri at Squaw Lake camp

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Cheri at Squaw Lake camp

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Squaw Lake ponds

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/6.3 at 24mm iso100

Sunset at Squaw Lake

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/160s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Sunset at Squaw Lake

- 1 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/60s f/4.0 at 24mm iso200

Indian paintbrush at our 9th campsite

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

One of many stream crossings

- 3 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1000s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Marie Lake, our 10th campsite

- 3 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/4000s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Flowers at Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/8.0 at 24mm iso200

Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/160s f/6.3 at 24mm iso200

Cheri at Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Tom at Marie Lake

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Cheri

- 3 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/50s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Cabin door near Muir Trail Ranch

- 4 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/40s f/3.2 at 24mm iso100

Crossing Evolution Creek

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Our swim spot in Evolution Creek

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Post-swim Cheri

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/2000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Evolution Lake

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Cheri at Evolution Lake

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1600s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Evolution Lake camp (night 11)

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/125s f/5.6 at 24mm iso100

Sunset at Evolution Lake

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso200

Sunset at Evolution Lake

- 5 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/720s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Sunrise at Evolution Lake

- 5 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/5.0 at 24mm iso400

Crossing at Evolution Lake inlet

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Evolution Basin

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Evolution Basin

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Evolution Basin

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Evolution Basin

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Muir Pass

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Muir Pass shelter

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Muir Pass shelter

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/640s f/13.0 at 24mm iso400

Muir Pass

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1000s f/16.0 at 24mm iso400

Descending from Muir Pass to Le Conte canyon

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Le Conte canyon

- 6 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/3200s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Le Conte rock monster

- 6 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/160s f/6.3 at 24mm iso100

Climbing to the Palisades

- 7 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2700s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Climbing to the Palisades

- 7 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Palisade Lakes

- 7 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso200

Palisade Lakes

- 7 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Flowers on Mather Pass

- 8 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Mather Pass

- 8 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso400

Cheri on Mather Pass

- 8 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1800s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Upper Basin

- 8 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2700s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Pinchot Pass

- 9 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Far side of Pinchot Pass

- 9 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

On our way to Woods Creek

- 9 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Woods Creek bridge

- 9 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/160s f/6.3 at 24mm iso100

South Fork Woods Creek

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1600s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

South Fork Woods Creek

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Rae Lakes Basin

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Rae Lakes Basin

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Rae Lakes ranger station does not have wifi

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Rae Lakes

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Rae Lakes (camp 17)

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/6.3 at 24mm iso200

Rae Lakes (camp 17)

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso200

Rae Lakes (camp 17)

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso200

Cheri at Rae Lakes

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/160s f/6.3 at 24mm iso200

- 10 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Morning visitor

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/125s f/5.0 at 24mm iso1600

Sunrise on Glen Pass

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/5.0 at 24mm iso800

The Painted Lady

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso400

Glen Pass

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Cheri on Glen Pass

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Cheri on Glen Pass

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Above Charlotte Lake

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Bullfrog Lake

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

The view south from Kearsarge Pass

- 11 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2900s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Descending to Onion Valley

- 11 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Onion Valley, biggest hole in the butt yet

- 12 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/120s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso40

Mule train

- 12 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1150s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Big Pothole Lake, near Kearsarge Pass

- 12 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Bullfrog Lake

- 12 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Bubbs Creek

- 12 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Last of our food

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/30s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Climbing toward Forester Pass

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso100

Climbing toward Forester Pass

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Gun show at our camp below Forester Pass

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Junction Peak

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Junction Peak

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso400

Dusk on Junction Peak

- 13 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/13s f/8.0 at 24mm iso800

Forester Pass

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Forester Pass flowers

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Forester Pass

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Cheri on Forester Pass, highest point on the Pacific Crest Trail

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

View south from Forester

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Cheri on Forester Pass

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Forester Pass flowers

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Far side of Forester pass

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/5.0 at 24mm iso100

Tyndall Creek basin

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Bighorn Plateau

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Bighorn Plateau

- 14 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/2700s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

From Bighorn Plateau, our first view of Mt. Whitney

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Mt Whitney

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Rest break on the Bighorn Plateau

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Bighorn Plateau

- 14 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Getting close to Whitney

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Guitar Lake

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Dinner at Guitar Lake (camp 22)

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Dinner at Guitar Lake (camp 22)

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Dinner at Guitar Lake (camp 22)

- 15 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1150s f/2.4 at 2.15mm iso50

Moonrise over Trail Crest

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Sunset at Guitar Lake

- 15 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Summit trail junction

- 16 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/15s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso1600

Pre-dawn light on the Mt. Whitney ridgeline

- 16 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/25s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso250

Cheri on Mt. Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/100s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Tom on Mt. Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Cheri shoots a summit sunrise selfie

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso400

Sunrise over Lone Pine

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso400

View southwest from Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso400

Sunrise on Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso400

Cheri on Mt. Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/2000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Summit register

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

USGS survey marker

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/2000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Mt. Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/2500s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Mt. Whitney summit

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

Descending from Mt. Whitney

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/9.0 at 24mm iso200

Descending Mt. Whitney ridgeline

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso200

Cheri's hero shot on the Mt. Whitney ridgeline

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso200

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso200

Mt. Whitney trail

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/200s f/7.1 at 24mm iso200

Back at summit trail junction

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/7.1 at 24mm iso200

Back at summit trail junction

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/125s f/5.6 at 24mm iso200

Trail Crest

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso200

Gun show at Trail Crest

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/1000s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Trail Crest

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Cheri on the Mt. Whitney Trail

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/3200s f/2.8 at 24mm iso100

Mt. Whitney trail

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Mt. Whitney trail

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/400s f/10.0 at 24mm iso100

Mt. Whitney trail

- 16 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/320s f/9.0 at 24mm iso100

Descending to Whitney Portal

- 17 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Descending to Whitney Portal

- 17 July 2016

- iPhone 5s

- 1/1100s f/2.2 at 4.15mm iso32

Whitney Portal

- 17 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Whitney Portal

- 17 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/250s f/8.0 at 24mm iso100

Whitney from the highway

- 18 July 2016

- Canon Rebel XT

- 1/80s f/8.0 at 24mm iso400